Atlantic Whitefish (Coregonus huntsmani)

Photo credit: Bob Semple

One of Canada’s most endangered species

Atlantic Whitefish (Scientific: Coregonus huntsmani; French: Corégone atlantique; Mi’kmaw: Kpqalme’j) is a member of the salmonid family that includes salmon and trout. It is also one of Canada’s rarest and most endangered wildlife species. Its current global range is limited to a single small watershed in Nova Scotia, Canada. The number of adult Atlantic Whitefish surviving in the wild is unknown but is unlikely to be more than a few hundred. It could be considerably fewer.

By the time Atlantic Whitefish gained official scientific recognition as a distinct species it was only known to occur in two non-adjacent watersheds in southwestern Nova Scotia: the Tusket/Annis River drainage near Yarmouth, and the Petite Rivière near the town of Bridgewater (Figure 1). By 1982 it had vanished from the Tusket/Annis system, leaving the Petite Rivière as the sole surviving population of the species.

Historically, Atlantic Whitefish were anadromous: juveniles and adults roamed coastal marine waters around southwestern Nova Scotia before returning to fresh water to spawn in the autumn. It is assumed that like other salmonid species, Atlantic Whitefish exhibited natal philopatry, that is, they returned to spawn in the same freshwater location in which they were born.

Figure 1 Historical range of Atlantic Whitefish. Image sourced from DFO (2018).

Written by P. Bentzen and S. Beal, August 2022Significance

Little is known about the distribution, abundance, ecological and cultural significance of Atlantic Whitefish before settlement of Nova Scotia by people of European ancestry. The tiny, disjunct freshwater distribution of the species in the 20th century may have been the result of early extirpations in other Nova Scotia drainages driven by widespread damming of southwest Nova Scotia rivers during the 18th and 19th centuries [1]. Anadromous Atlantic Whitefish remained abundant in the Tusket/Annis system as recently as the middle decades of the 20th century. It is reasonable to speculate that in previous centuries Atlantic Whitefish spawned in many Nova Scotia river systems, and that juvenile and adult Atlantic Whitefish played a significant ecological role in coastal marine waters around southwest Nova Scotia.

Figure 2 Divergence of Atlantic Whitefish (C. huntsmani) from common whitefish ancestor. Image sourced from Crête-Lafrenière et al. (2012).

Atlantic Whitefish are related to dozens of other species of whitefish found throughout the northern halves of North America, Europe, and Asia. Collectively, this group of species has considerable ecological, cultural, and economic importance as important components of northern freshwater biodiversity and as highly valued food fishes.

The anadromy that was once an integral part of the Atlantic Whitefish life cycle is an uncommon trait in whitefishes. Most species occur only as freshwater populations; only a few species in a few regions are known to deliberately migrate to the sea.

Atlantic Whitefish has considerable evolutionary and scientific significance as the sole surviving representative of a lineage that diverged from other whitefishes as much as 14 million years ago (Figure 2) [2]. Most other whitefish species, and indeed most wildlife species endemic to Canada, have much more recent evolutionary origins.

Threats

A combination of factors, including poaching, acidification, invasive predatory fishes, and dams with inadequate fish passage are believed to have caused the extirpation of Atlantic Whitefish in the Tusket/Annis drainage. For more than a century, dams in the Petite Rivière system also prevented the local Atlantic Whitefish population from completing its natural anadromous lifecycle; however, the Atlantic Whitefish there survived by completing their lifecycle entirely in fresh water in three interconnected lakes: Milipsigate, Minamkeak, and Hebb. These lakes, which have a combined area of only 16 square kilometres, represent the current total global range of the species.

In 2012, a fish passage facility was added to the tallest of the Petite Rivière dams, the Hebb Lake dam, but apart from 19 adult whitefish in 2012, no Atlantic Whitefish have been observed using the fish passage in the past decade (Figures 3-6).

The Petite Rivière habitat of Atlantic Whitefish has been invaded by two non-native predatory fish species, Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieu; Figure 7) and Chain Pickerel (Esox niger; Figure 8). Both species are threats to the population, but Chain Pickerel, which was first detected in the Petite Rivière lakes in 2013, is of particular concern. There is a substantial risk that, if left unchecked, this predator could eliminate Atlantic Whitefish from its remaining habitat, and thereby drive the species to extinction. So far, Chain Pickerel have been found in two of the three lakes that harbour Atlantic Whitefish, Hebb and Milipsigate.

Recovery efforts

In 2018, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) established a three-tiered recovery plan for the species: establishing a stable population, expanding the current range, and restoring anadromy [3].

To support the remaining population, electrofishing is conducted annually to reduce the abundance of Chain Pickerel and Smallmouth Bass in the Petite Riviere lakes. Electrofishing stuns but does not kill fish, allowing the two invasive species to be removed without harm to native fishes. This program has succeeded in reducing numbers of bass and pickerel in the Atlantic Whitefish habitat but will require continued efforts to keep the predator populations as low as possible.

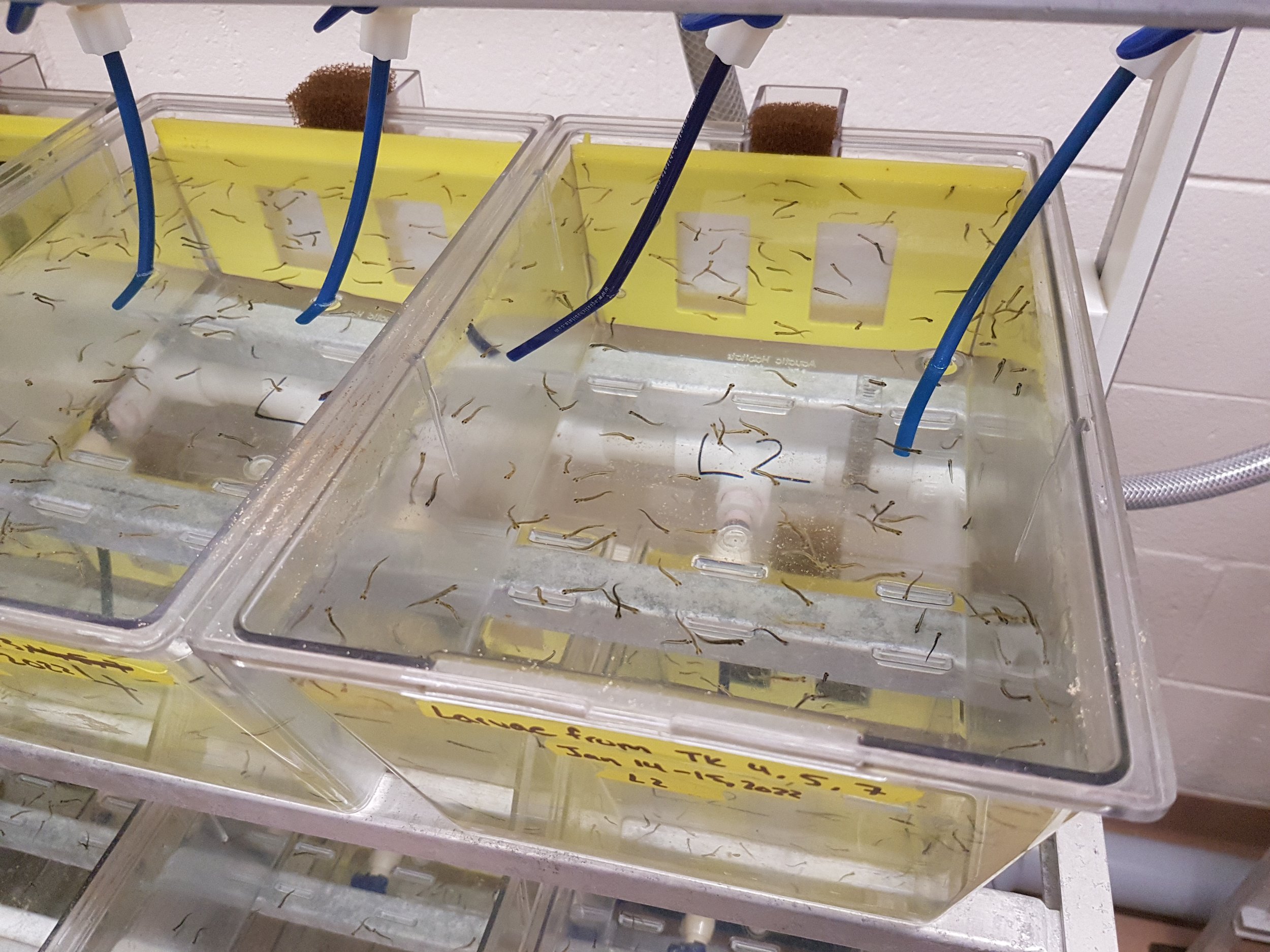

Since 2018, Atlantic Whitefish captured annually in the spring as newly free-swimming larvae in the Petite Rivière lakes have been brought to the Aquatron facility at Dalhousie University where they are being reared for captive breeding to support species recovery efforts. The objective is to release captive-bred juvenile whitefish back into the Petite Rivière system with the goal of increasing the population and re-establishing the anadromous life cycle. The first spawning of captive Atlantic Whitefish in the Aquatron occurred in the winter of 2022 (Figure 9), and in June and July of that year the first releases of juvenile whitefish were carried out.

The plan is to continue breeding Atlantic Whitefish in the Aquatron and to continue the annual releases of juvenile whitefish in the Petite Rivière system. Additional plans include introducing captive-bred Atlantic Whitefish to other locations in Nova Scotia with the goal of further securing the species by expanding its range.

Figure 9 Atlantic Whitefish larvae born at Dalhousie’s Aquatron Facility in 2022. Photo credit P. Bentzen.

Research

Research is being carried out in the Bentzen lab and the Dalhousie Aquatron to support the recovery of Atlantic Whitefish and learn more about the biology of the species.

Previous research showed that despite their many generations lived exclusively in fresh water, Atlantic Whitefish from the Petite Rivière population retain the ability to live in seawater; in fact, experiments showed that the juvenile Atlantic Whitefish seemed to prefer salt water over fresh water [4]. Ongoing research will exam growth, swimming performance and physiological parameters in Atlantic Whitefish living in different salinities.

A major focus of research in the Bentzen lab is the development and use of environmental DNA (eDNA) methods to monitor the presence and distribution of Atlantic Whitefish in the wild. Given the small number of Atlantic Whitefish that remain in the wild, methods that monitor the species need to be highly sensitive and non-invasive. Conventional eDNA-based methods meet these criteria, but even so, can fail to detect Atlantic Whitefish at the extremely low abundance at which they currently occur. The Bentzen lab is developing methods that improve the sensitivity of detection over previous eDNA methods. Our eDNA tools will help close gaps in current knowledge of Atlantic Whitefish biology, such as the location of spawning and other critical habitats in different seasons of the year – and in the future, perhaps, how it uses marine and estuarine habitats.

The ancient origins and unusual ecology of Atlantic Whitefish make it important to investigate its genome. In collaboration with the Bradbury Population Genomics lab we are currently sequencing the Atlantic Whitefish genome.

References

Themelis, D.E., Bradford, R.G., LeBlanc, P.H., O’Neil, S.F., Breen, A.P., Longue, P, and Nodding, S.B. 2014. Monitoring activities in support of endangered Atlantic Whitefish (Coregonus huntsmani) recovery efforts in the Petite Rivière lakes in 2013. Can. Manuscr. Rep. Fish. Aquat, Sci. 3031. v + 94 p. https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/351808.pdf

Crête-Lafrenière A, Weir L, Bernatchez L. 2012. Framing the Salmonidae Family Phylogenetic Portrait: A More Complete Picture from Increased Taxon Sampling. PLoS ONE 7(10):e46662. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046662. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0046662

Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2018. Amended Recovery Strategy for the Atlantic Whitefish (Coregonus huntsmani) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. xiii + 62 pp. https://novascotia.ca/natr/wildlife/species-at -risk/docs/RECOVERY_PLAN_Adopted_Atlantic_Whitefish_22February2021.pdf

Cook, A.M., R.G. Bradford, B. Hubley, and P. Bentzen. 2010. Effects of pH, Temperature and Salinity on Age 0+ Atlantic Whitefish (Coregonus huntsmani) with Implications for Recovery Potential. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2010/055. vi + 47 p. https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2010/2010_055-eng.htm